Prickly Pear

Prickly pear is my least favorite cactus to run into, tip over into, step on, etc. The spines usually break at the skin's surface, leaving about a cenimeter of unbroken spine in your flesh. The last time I had a bad encounter with a prickly pear, I went straight to Urgent Care after my ride and asked the PA on duty to please take a scalpel and remove them from my flesh. To my surprise, he was agreeable to the task. Yeah, prickly pear pretty much suck.

Except for late July into August.

It's that time of year again, and another attempt at making prickly pear jam. We headed out to our patch of desert we harvest the fruit from as in years past.

Not all of it was as ripe as hoped, but we harvested anyway as the inside of the fruits was that unmistakabe, rich magenta of fully ripened fruit. Still...the outside color on about a quarter of what we picked was still a bit green.

Back home in the kitchen, we prepared the fruit by first floating them in a sink of hot water to wash off the ants, spiders, twigs and spines that are inherent in harvesting prickly pear fruit.

We then placed them in a pot and brought just to boil and then removed them from heat.

Next, We ran them through our Breville juicer, which does an adequate job of separating seeds from juice. I also like this juicer because it allows for fine pulp to pass the screen. The juice was placed in a stockpot, and was mixed 4 juice with the juice from two lemons, added the pectin, and brought to a boil. Immediately removed from heat, added in 6 cups sugar, brought to a second boil and immediately removed from heat.

We ladled the thickened syrup into sterilized 8-oz Kerr jars, capped them and screwed on the rings. Within minutes the lids began to pop. Once cooled to room temperature, we placed the jars in the fridge and hoped for the best. In all of our previous years'attempts, we only ever ended up with syrup. NOT this time! The jam from the first batch set beautifully, and we ended up with a case and a half of jam! We had a lot of leftover syrup which I froze to can the following weekend.

ended up with syrup. NOT this time! The jam from the first batch set beautifully, and we ended up with a case and a half of jam! We had a lot of leftover syrup which I froze to can the following weekend.

Well, that following weekend, I did everything as I had done before except add lemon juice (I forgot to be honest). This batch did not set, but rather resulted in a very thick prickly pear sauce which tastes great.

The following weekend, I decided to try making sorbet with the prickly pear sauce. Using our Cuisinart ice cream maker, I added 16 oz of prickly pear sauce and 24 oz of water and let it churn for about 25 minutes.

The result was a very tasty sweet/tart prickly pear sorbet--SUCCESS!

PR-2020

12 Hours of Mesa Verde

Mountain Bike Race

May 13, 2017

Cortez, Colorado

The gun went of at 0700AM, and Jamie and 200 other racers hit the trail for the Le Mans start, running the first quarter mile to where their bikes were staged. I was grateful to Jamie for taking the first lap, as I can't run to save my life (it's why I ride a bike, barely). There were a total of 850 racers.

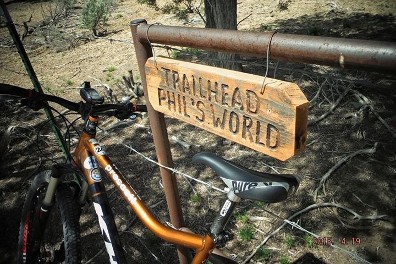

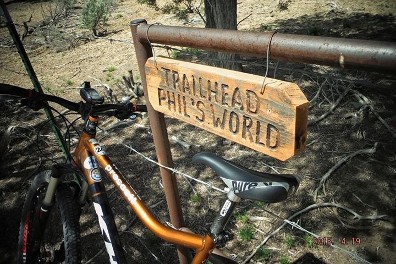

The race was on Saturday. Thursday, after Mike and I and the pups Kodi & Hudson arrived in Cortez, Colorado, I met up with Jamie to pre-ride the 12 Hours of Mesa Verde race course. The race takes place at Phil's World right outside of Cortez, and winds through 18 miles of twists and turns, rolls and ledges, climbs and descents. And views.

I seemed to have legs for the pre-ride of the course. The same would not be true on race day.

On Friday, Osprey had their locals-only sale at their factory warehouse. It was like being a kid in a candy store! At Christmas!! We went and stocked up on backpacks, day packs, hydration packs and a computer pack, and well below retail. It was a really cool surprise to find out that we happened to be there on the right weekend!

Friday evening, we had dinner with Jamie and Lara at their home in Cortez. While Jamie and I were in the driveway and front yard wrenching on bikes in preparation for the race, Kodi decided to drop in on me and see what I was doing...from the second story. I saw a white blur fly past my head, and turned just in time to see Kodi land on all fours in the grassy front yard. He had somehow jumped far enough out from the house to clear the front sidewalk. I was stunned, and so thankful he didn't hurt himself in the process. So we now know we have a flying dog, and need to be mindful of that.

Saturday morning, race day. We were team "LHUSSx2," Lock Haven University Single Speed times Two. Team #309.

Jamie turned in a first lap of just over one hour thirty minutes. My first lap, however, was two and a half hours. Jamie continued turning in respectably-timed laps. My second lap out, I had to stop and tighten up the Surly Singleator (do NOT ever buy this piece of equipment for your singlespeed--they are too fragile for even low-impact single speed rides. This was the third one I have had, and will steer clear of them in the future. After I was back on the bike a short time later, I bonked. Out of sugar, out of gas, legs just quit. I sat to the side of the trail chewing down gummy Life Savers, chugging Half Evil 333, both of which helped after a few minutes. But by then, I was woefully behind, being passed right and left by other riders, which also had the effect of slowing me down even more. It took me nearly three hours to finish my second lap. When I got back to the relay tent, Jamie went off for his third and final lap. I was mentally spent, and knew that I was done. Not how I wanted to finish my first 12HOMV race, but that's how the chips fell.

In the end, I had a great time, and the best racing partner. Thanks, Jamie for the chance to race and for the experience. I will put this on the calendar for next year!

(photo from April 2015)

Kokopelli Trail, May 22-24, 2014

Bucket lists. We all have them in one form or another. Problem with mine is that I'm sticking gotta-do's in my bucket faster than I'm pulling them out. I need a bigger bucket. Or many more decades. Or I simply need to make more of an effort to get off my ass, get out there, and just do it.

I had wanted to ride Kokopelli's Trail since the mid 90s, when I had first heard of it. At the time, I was living in Denver, and roadtripping to Moab every 6 months or so had become a ritual, sometimes with friends, sometimes solo. I promised myself that one day, somehow, I would get back to ride this trail. I didn't know when, I didn't know how, and I didn't know with whom. But I WAS coming back, and I WOULD ride this trail.

In May, 2014, I was struggling with the onset of another vicious descent into a depressive cycle. Yes, I stuggle with depression. The bike helps. But this descent was proving to be one of the deeper ones, with its consummate cold, greasy inevitability. Something had to happen before the usual unilateral relationship damage and damage to self that accompanies such episodes with certaintude. Depression is a ruthless bitch, and one some families and their descendents just have to fight. There is no slaying this dragon. It rides shotgun always, shows up on a schedule, and leaves begrudgingly. While at its peak, relationships wither and strain, friendships get tested, sometimes beyond the breaking point. And here I was, out on this awful precipice, staring into an oblivion I was all too familiar with. I needed to get away, out of the house, away from Mike, and away from my friends.

Things came together quite quickly to fulfill this promise to myself, to cross the Kokopelli off the list. I grabbed bike and gear and headed north on Thursday, May 22. Earlier in the week, I had made arrangements with Coyote Shuttle in Moab for a lift from Moab to the trailhead in Loma, Colorado that Thursday afternoon. I got to Moab sooner than I had expected, and their driver was available to leave early, meaning I would be able to get some miles in Thursday afternoon before nightfall--bonus!

I packed as lightly as I thought I could. The weather was a crap shoot, and with the forecast deteriorating in the days leading up to my ride, I chose to pack a lightweight waterproof shell, one pair of clean socks, arm warmers, a knit cap, and mittens. I took it on faith that I wouldn't freeze my ass off. My gear:

Handlebars--

- ground tarp

- inflatable sleeping pad, bivy sack,

- sleeping baga

- GPS and camera mounts;

Frame bag--

- 4-liter MSR water bag

- tool kit

- tire wrenches, multi-tool, two rubber boots, spare tube, one set brake pads, spare presta stem, presta valve core wrench, chain tool, master link, derailleur hanger, Leatherman Wave, 4 oz. Stans magic juice, five 20 dollar bills...

- riding lights and batteries;

Rear seat bag-

- clothes

- water filter

- stove

- pillow

Jolla Hydrapak--

- 3 liters of water

- three dehydrated dinners

- three dehydrated breakfasts

- one-pound bag of beef jerky

- six all-natural energy bars

- nine individual packs of HEED drink mix (I forgot to place a Carbo Rocket order in time, dammit)

- toilet paper ( + ziplock bag--pack in, pack out folks)

- portable USB charger

- spare GPS batteries

Back jersey pockets--

Fully loaded, the bike cashed in at 49.3 pounds, heavier than I had hoped, and this did not include the additional 9.6 pounds on my back. But you can never carry too much water on an unknown trail, and though the map indicated water crossings and/or close proximity to water, access was a big unknown.

The Kokopelli starts out climbing the hogbacks that separate I-70 to the north and the Colorado River to the south. It is a long climb with short bouts of descent to catch your breath, but then the sweeping views take that breath away again. It was more technical out of the starting gate than I had anticipated, but I was up for anything she could throw my way. I WAS doing this! There aren't words to describe the sense of exhilaration and triumph just to be starting off by myself into the unknown. No real schedule to keep (other than get back to Moab by Sunday), no one to slow down or to feel I had to keep up with, no competing agendas, no conflicts. Just me, my bike, and the big, wide world. I felt smaller than a speck in the vastness.

The following paragraph may be unsuitable for some readers; reader discretion is advised. I became a believer in chamois butter on the Death Valley trip. DZ Nuts, specifically. Good stuff. In prep for this trip, I picked up a new tube. Just prior to jumping on my bike and heading into the great unknown, I applied liberally to my nether regions, and set off. Within 500 feet, I was trailside frantically stripping off my bibs, using my arm warmers and drinking water to extinguish the hellish fire that was consuming my crotch. Turns out, I had mistakenly grabbed a tube of DZ Nuts embrocation cream, definitely NOT something you want anywhere near the frank and beans. I was in agony. Even after wiping as much off as I could and changing to new bibs, I felt like I was being punched in the balls for the first five or six miles. Lesson learned. Read labels.

And now back to our regularly-scheduled programming...

I rode until the sun had dropped below the horizon, and set up my first camp in a small meadow capping a mesa that overlooked the Colorado River. As I was drifting off to sleep, the stars were out in full-on glory, and I even spotted a stray meteor from the much-hyped upcoming Camelopardalids meteor shower, supposing to peak on May 24. I drifted to sleep under a resplendent Milky Way. Five hours later, I would be awakened by lightning and approaching, rumbling thunder.

I slept fitfully for the rest of the night, and when it began raining at about 3 a.m., I scrambled to pull all of my gear into my bivy with me. Tight fit, and I never imagined I would ever be spooning with my gear, but no sense in taking the chance of soaking everything my first night out. Fortunately, the rain that first night was light and intermittent, and I was greeted at sunrise by gold and velvety-pink rays of sunlight straying through off-and-on sprinkles.

Breakfast was Mountain House scrambled eggs and bacon...and no coffee? True, I forgot to pack the Via. Never again! So HEED became my breakfast beverage. Not as satisfying as a hot cup of coffee. Just...not. I loaded up the bike and was off.

The morning started with a short climb followed by a phenomenal descent to Salt Creek. I replenshed my water supplies at Salt Creek. Laden with silt from the Book Cliffs upstream, the water was swift, cold, and DENSE. I wrapped the intake of my water filter with a clean dew-rag to pre-filter out the sediment. No sense in clogging it up on Day One, with so much unknown yet to come. I am now a believer in water filters regardless of whether or not you "know" the availability of water. They are essential to bikepacking, even long rides here at home where watersources are fairly certain (think Black Canyon Trail at the Agua Fria crossings, or AZ Trail cattle tanks and Gila River, for instance, heck, even water-filled tire ruts on forest roads).

The climb up and out of Salt Creek Valley back to the top of the plateau was what can best be described as a soul-sucking grind, and by the time I topped out onto Rabbit Valley Road, the rain became steady. Fortunately I had climbed through the Chinle Formation by then, so I was above and beyond what would have been gear-eating mud. The rain became more insistent as I pedaled towards Rabbit Valley and the Utah border. The temperature dropped into the upper forties, and unwelcome gusts blew the rain stingingly sideways. About two miles before crossing into Utah, the rain was too heavy to continue. I took shelter under a juniper with my tyvek ground tarp over my head and waited out the storm. Half an hour later, the sun began poking holes in the clouds' rainy day arguments, the temperatures rose twenty degrees, and the rest of the day would prove glorious.

Kokopelli's Trail through Rabbit Valley is a balls-out big ring hammer fest. What a way to lift the spirits!

Along the trail, there comes a junction with two options: head north on the Kokopelli for a loop around Harley's Dome, or continue heading westerly on a section of the Western Rim Trail to rejoin Kokopelli near Westwater. After studying the map and judging by topography, I chose the Western Rim route. Quite soon into this section, I knew I had made the right decision. The views were enormous, the trail flirted with a 500' edge above the Colorado River, and the next seven miles were punctuated by enough technical sections to keep me off my seat, on my toes, and laughing to myself. It is the kind of scenery that, for reasons I can't explain, brings soulful tears to my eyes. The Kokopelli had many such emotional sections for me. It comes from somewhere else.

The Kokopelli has multiple loops stemming from it. Even with a GPS, it is easy to become disoriented in places. Right above Westwater is one of them. I rode out and backtracked the same wrong section twice, each time convinced it was the right way, and each time further off course. I burned valuable daylight re-orienting myself and getting back onto the correct route. As I reached pavement at Westwater, the clouds were gathering, and it began to look as if there would be no escaping another round of rain. Little did I know what was to come.

A few miles on, and the Kokopelli transitions from pavement (Westwater Road) back to dirt. About two miles along the dirt road, the thunder had grown more menacing, the sky had acquired a bruised, greenish hue, and sudden gusts of wind sandblasted by legs, arms, and face, and made staying upright and on trail impossible. The landscape was disappearing to my south behind a veil of heavy rain. Decision time, and quickly! I stopped, set up camp and hunkered down for the impending storm, and not a moment too soon. Just as I was putting the last of my gear into the bivy, the rain began to fall in big, cold drops. Drops so large they are in shreds by the time they hit with a SPLAT! I burrowed in to my bivy just as all hell broke loose. It was just 6 p.m., easily two to three more hours of riding, except for this. Lightning was fast and furious, and thunder was either instantaneous or within a second or so of the flash. It was terrifying and wonderful. And then it did not stop. The lightning and thunder moved on, but the rain and the wind persisted until after dark. There would be no more riding tonight. The last thing I wanted was to get disoriented in the storm, bogged down in wet, sticky Chinle, or swept away in a flash flood.

I awoke before the sunrise to a clear sky. I watched the last of the stars and planets wink out as the sun approached the horizon. Its perfect light cast on the surrounding cliffs, mesas and buttes, on the wet grass before me, was magic. Wet. Wet was NOT magic. Despite my bivy's waterproof material, my down sleeping bag had soaked through where it had been in contact with the inside of my bivy. In fact, everything in my bivy was some shade of damp. While my Mountain House beef stroganoff and noodles was cooking up in its bag for breakfast, I used the nearest juniper bush as clothesline to dry out my wet sleeping gear as much as I could. My concerns were twofold: because of being socked in early from the previous night's storm, I hadn't made the miles I had hoped to make. And this coming night would require climbing to over 8,000 feet, which surely had gotten snow out of this storm system. A down bag has so many advantages to synthetic bags...but retaining warmth while wet is not one of them. Another decision. I would cross that bridge when I came to it.

I caught my first glimpse of the Manti La Sal Mountains soon after replenishing my water from a generous cattle pond just off the trail. They seemed so distant! Snowcapped and mighty, they were today's destination, and would serve as my landmark the rest of the ride.

The trail between Westwater and Cisco Landing is mostly maintained dirt road with a short paved section at Cisco Landing. Big ring cruising! What a rush after so many technical sections the previous day! The La Sals were closer with each passing mile. After Cisco Landing, the Kokopelli leaves pavement to follow the suggestion of a jeep track. It climbs up and over the Chinle, and at the summit, I found myself staring down at the Colorado River, now mighty, coursing its way downcanyon, always around the next bend, always out of sight. The trail drops to the river, and meanders along its northern bank for several miles until it climbs abruptly to the top of the adjacent stream terrace. From here, it's a short sprint to UT-128, the "River Road," and Dewey Bridge, the last crossing of the Colorado on this trail, a bit more than the halfway mark, and with the still-wet gear, decision time.

As I got to Dewey Bridge, the clouds that the La Sals had been calving all morning were beginning to coelesce into the coming afternoon's line of thunderstorms. So staying dry would not be an option for sure. Discussions with a few people at Dewey indicated snow above 8,000 ft as I had imagined, and I simply was not prepared for a night near freezing, not with wet gear. It was not an easy decision, but it was the right call. I would save the Manti La Sal and Porcupine Rim section of the Kokopelli for next time. I had completed 72 miles of some beautiful, difficult terrain, and I still had 30 miles of pavement along River Road back to Moab. And not easy miles with a headwind, more rain and all the hills I had forgotten about!

With 17 miles to go, my body was completely out of gas. All I could think about was getting my hands on a Coke. Into view came Sorrel River Ranch, an emerald nirvana in all the redrock canyons. I have passed this place dozens of times over the past two decades, mostly on pavement, and once rafting down the river. But I had never noticed the "Restaurant & Resort" sign before. I had always assumed it was a working ranch (it is). Restaurant meant Coke. I headed down the long driveway to the big ranch house. Sure enough, the restaurant WAS open! Not only did I have at least ten glasses of Coke, but I added two large bowls of Elk Bolognese rigatoni to my growling stomach. Got to feed the machine! Tom and the rest of the folks at Sorrel River Ranch? Thanks! That was just what I needed to hammer out those last 17 miles to Moab.

I got back to my truck around 3 that afternoon. There have been many rides that I have been both very glad to finish but sorry to see them end. Not in this case. This was truly the first ride that I was sad to finish, and was sad it was over. Though it isn't truly over, not yet. There is still the high-country section to ride, and that will be sometime later this year. Still, crossing Kokopelli off the list was bittersweet. I have looked forward to this for so long. It was everything, many things and more than I could have expected. It DELIVERED. And just like that, it was over. But it wasn't "just like that." It was an ass-busting ride! Not an easy undertaking, and certainly not one to be taken lightly.

Elation and melancholy, memories of my time out there, just me, my bike, the trail, the sky. And though it is now officially "half-off" of the Bucket List, the Kokopelli is now ensconced on my list of "trails to do again." I'll be back to hit the La Sal/Porcupine Rim section later this year. And I'll be back to ride through again one day.

Photos

PLR-01JUNE2014

JUNE 2011

Their Places We Call Home

I left the house around 5:30 this afternoon for my routine ride after work, on the trails that reach beyond the pavement and suburban order of Gold Canyon, AZ. I look forward to these after-work rides even more than sometimes I realize. Lately it’s all I can do to clench my teeth and endure the Monday through Friday grind. What gets me through is knowing that all the demands and stress of the day will melt away with each passing minute in the saddle, clipped in to my pedals, listening to the crunch of dry gravel beneath my tires, the wind and the rush of blood in my ears, the mechanical clicks and creaks of my trusty Rockhopper, and all the diverse and varied sounds the desert makes that create the soundtracks of my rides. I can shut down, and focus on just the here and now and truly be present in the moment, unlike at any other time of my day. And I am free to think freely.

There is currently a debate unfolding in an online mountainbike forum to which I subscribe, and occasionally to which I post. The question was posed (as it is inevitably every spring) whether or not it is morally correct to kill rattlesnakes when we encounter them on the trail.

I’ll get my position out of the way right up front: personally, nothing justifies killing a rattlesnake out on the trail. I realize that this statement is enough to start a bar fight, cause premature hair loss and lead to divorce. This issue clearly divides us humans into one of two camps. There are those that think rattlers have a right to exist and should just be left alone and appreciated from a safe distance, and then there are those that are rooted in the conviction that rattlers should be—must be—exterminated from the face of the Earth.  Their reasons vary, but usually include concern for wives, kids and pets (yes, that sounds sexist, but I’ve only ever heard the males of our species make the argument…their wives having more sense, usually). One of my online fat-tire brethren insists that we have a moral obligation to kill any rattler we encounter on the trail in order to spare those who come after us from a dreadful bite, an excruciating death and insurmountable medical bills even though the next passerby would most likely have enough sense to leave the snake alone. I certainly do NOT grant anybody the authority to "look out for my wellbeing" in such fashion. I don’t know what compels such animosity, but I have a sneaking suspicion that it has less to do with moral imperatives and selfless acts of heroism on behalf of strangers, and more to do with fear, a hyper-inflated comprehension of the actual risk, a primal desire to kill stuff, and even a mystical religious bias against snakes in general. You HAD to eat the apple, didn't you, Eve?

Their reasons vary, but usually include concern for wives, kids and pets (yes, that sounds sexist, but I’ve only ever heard the males of our species make the argument…their wives having more sense, usually). One of my online fat-tire brethren insists that we have a moral obligation to kill any rattler we encounter on the trail in order to spare those who come after us from a dreadful bite, an excruciating death and insurmountable medical bills even though the next passerby would most likely have enough sense to leave the snake alone. I certainly do NOT grant anybody the authority to "look out for my wellbeing" in such fashion. I don’t know what compels such animosity, but I have a sneaking suspicion that it has less to do with moral imperatives and selfless acts of heroism on behalf of strangers, and more to do with fear, a hyper-inflated comprehension of the actual risk, a primal desire to kill stuff, and even a mystical religious bias against snakes in general. You HAD to eat the apple, didn't you, Eve?

Let’s be honest. Rattlesnakes can be scary. Sometimes they scare me. They can make my heart rate spike, they can flip some fear-response switch in my primordial brain. But rattlesnakes don’t go out of their way to bite people. First of all, it takes a rattlesnake a lot of time—days—and energy to generate venom, and a rattler would much prefer to use it to capture its next packrat or lizard or baby bunny than to waste it on gangly, two-legged ungraceful monstrosities many, many times its size that it could never possibly eat. They strike to eat and if necessary to defend, but they do not strike to attack. They are not strategic, cunning man eaters. Second, rattlesnakes can only strike with accuracy within a distance 2/3 its length. In order to get bit, a person must place their hands (the most usual limb to get bitten, for suspicious reasons) within 2 feet of a typical full-grown rattlesnake. Third, a rattlesnake has no arms, no legs, no other possible way to defend itself other than through its bite. Don’t give a rattlesnake the opportunity, and it isn’t going to bite. Finally, in more than half of snakebite incidents, the “victim” was doing something stupid. And getting close enough to a rattlesnake in order to kill it is stupid.

Let’s be honest. Rattlesnakes can be scary. Sometimes they scare me. They can make my heart rate spike, they can flip some fear-response switch in my primordial brain. But rattlesnakes don’t go out of their way to bite people. First of all, it takes a rattlesnake a lot of time—days—and energy to generate venom, and a rattler would much prefer to use it to capture its next packrat or lizard or baby bunny than to waste it on gangly, two-legged ungraceful monstrosities many, many times its size that it could never possibly eat. They strike to eat and if necessary to defend, but they do not strike to attack. They are not strategic, cunning man eaters. Second, rattlesnakes can only strike with accuracy within a distance 2/3 its length. In order to get bit, a person must place their hands (the most usual limb to get bitten, for suspicious reasons) within 2 feet of a typical full-grown rattlesnake. Third, a rattlesnake has no arms, no legs, no other possible way to defend itself other than through its bite. Don’t give a rattlesnake the opportunity, and it isn’t going to bite. Finally, in more than half of snakebite incidents, the “victim” was doing something stupid. And getting close enough to a rattlesnake in order to kill it is stupid.

Just how often do people encounter rattlesnakes out on the trail? I would guess I am a pretty average mountainbiker, and probably spend as much time as most out on the trails in the late afternoons, nights and early mornings of spring, summer and fall — the most likely times to encounter a rattlesnake. I rarely see them. I don’t think I have seen more than 20 in the 20 years I have been riding in Arizona. One a season is about it. This year, 2011, has been an unusual year. Since the beginning of April, I have encountered two on the trail, and one in the street out in front of the house. I attribute this to living adjacent to open desert, and now frequently riding in areas that don't see heavy mountainbike and hiking traffic. But again, this is unusual, and my sightings will probably taper off as summer lumbers on.

Just how often do people encounter rattlesnakes out on the trail? I would guess I am a pretty average mountainbiker, and probably spend as much time as most out on the trails in the late afternoons, nights and early mornings of spring, summer and fall — the most likely times to encounter a rattlesnake. I rarely see them. I don’t think I have seen more than 20 in the 20 years I have been riding in Arizona. One a season is about it. This year, 2011, has been an unusual year. Since the beginning of April, I have encountered two on the trail, and one in the street out in front of the house. I attribute this to living adjacent to open desert, and now frequently riding in areas that don't see heavy mountainbike and hiking traffic. But again, this is unusual, and my sightings will probably taper off as summer lumbers on.

So what’s the real risk? A quick consultation with The Google yields the following statistics. A person is nine times more likely to be struck by lightning than be bitten by a rattlesnake. That person, once bitten, is twenty times more likely to be struck again by lightning than die from their bite. According to a recent University of Arizona College of Pharmacy study, 50 to 70% of reptile bites managed each year by the AZ Poison Control Center were provoked by the person who was bitten—that is, someone was trying to kill, capture or harass the animal (stepping on a rattlesnake or accidently placing hands in harm's way is more likely to result in a "dry" bite, while molesting a rattlesnake gives it time to prepare to defend itself). Finally, of the approximately one thousand people who find themselves at the wrong end of a rattlesnake each year, less than five will die. In the United States, 150,000 people die each year from smoking-related lung disease. 50 people die from lightning strikes. 15 people die from being attacked by the family dog. 5 people die from rattlesnake bites. Fewer than five from black widow bites. Curiously, black widow spiders concern me more than rattlesnakes. It isn't uncommon to encounter black widows in the garage and around the yard, but I have yet to encounter a rattlesnake around or inside our home.

Poison Control Center were provoked by the person who was bitten—that is, someone was trying to kill, capture or harass the animal (stepping on a rattlesnake or accidently placing hands in harm's way is more likely to result in a "dry" bite, while molesting a rattlesnake gives it time to prepare to defend itself). Finally, of the approximately one thousand people who find themselves at the wrong end of a rattlesnake each year, less than five will die. In the United States, 150,000 people die each year from smoking-related lung disease. 50 people die from lightning strikes. 15 people die from being attacked by the family dog. 5 people die from rattlesnake bites. Fewer than five from black widow bites. Curiously, black widow spiders concern me more than rattlesnakes. It isn't uncommon to encounter black widows in the garage and around the yard, but I have yet to encounter a rattlesnake around or inside our home.

I often make the case that when we are out on the trail, we are in the rattlesnake’s living room, also the realm of the Gila monster, the scorpion, the javelina, the tarantula, mountain lion, the jumping cholla, all things elegant and beautiful and toothy and prickly and sometimes venomous. It begs the question, then, about how and where we humans fit in to this picture. As I ride, I have no good answer.

I often make the case that when we are out on the trail, we are in the rattlesnake’s living room, also the realm of the Gila monster, the scorpion, the javelina, the tarantula, mountain lion, the jumping cholla, all things elegant and beautiful and toothy and prickly and sometimes venomous. It begs the question, then, about how and where we humans fit in to this picture. As I ride, I have no good answer.

This much I know: I do want rattlesnakes in my desert. In fact, I need them in my desert. I go there partly to get out of my comfort zone, to see life from a very clear and different perspective. I need to know that they are out there, where they belong, serving their purpose in the endless duality of life and death, eat or be eaten, fight or flight survival in a hardscrabble place. I need to know that there is still an element of something wild, a creature that cannot be tamed, an animal far less in stature than I and yet demanding of perhaps greater respect. Without the rattlesnake, the desert isn’t wild, I am incomplete, and we are diminished.

Riding back home tonight, west into the setting sun (an honest cliché, really), thousands of strands of spider web spun slowly through the golden air, a spectral threadwork catching rainbows, and catching on my face, my arms, my handlebars and tires. Black widow hatchlings, tens or hundreds of thousands of them, were ballooning, sending skyward a single strand of the most delicate, pure gossamer web, stronger than steel, catching the breeze and flying off to new lives, new worlds, new single-parenting adventures. At some point in my childhood, I remember reading about the early days of the US space program. While sampling the upper atmosphere in the late 1950s, researchers found live spiderlings floating at nearly 100,000 feet, orbiting the blue-green Earth below. And as I was riding home tonight, into the sun and through the webs, thoughts of all these fantastic desert critters that inspire awe, fear and wonder, thoughts of odds and risk and likelihood were spinning out ahead of me. How do you sum up our relationship with the rattlesnake, the mystery of the desert, those that dwell within it, and our place among it all?

ballooning, sending skyward a single strand of the most delicate, pure gossamer web, stronger than steel, catching the breeze and flying off to new lives, new worlds, new single-parenting adventures. At some point in my childhood, I remember reading about the early days of the US space program. While sampling the upper atmosphere in the late 1950s, researchers found live spiderlings floating at nearly 100,000 feet, orbiting the blue-green Earth below. And as I was riding home tonight, into the sun and through the webs, thoughts of all these fantastic desert critters that inspire awe, fear and wonder, thoughts of odds and risk and likelihood were spinning out ahead of me. How do you sum up our relationship with the rattlesnake, the mystery of the desert, those that dwell within it, and our place among it all?

In a world where spiders were the first astronauts, I come up short, I smile, and I pedal. Home.

-PR

MARCH, 2011

"Wounds"

Riding a bike is not without risk. It takes a certain amount of skill and coordination to keep the thing balanced and moving forward. Most of the time things go well, the rubber stays down, the helmet stays up. But sometimes, well, shit happens. Everything can seem all right, under control and perfectly normal, but suddenly and before you know it, you’re inexplicably twisted up on the ground ahead of where your bike lay sideways on the trail. As adults, we can generally gauge the severity of our crashes by whether or not our friends are laughing at us or running towards us (this doesn’t necessarily hold true for adults younger than, say, twelve, who laugh at just about everyone else’s misfortunes). Most of the time we’re lucky, and we relive the crash in all its post mortem glory with irreverence and gusto. Sometimes, though, we’re not so lucky.

Riding a bike is not without risk. It takes a certain amount of skill and coordination to keep the thing balanced and moving forward. Most of the time things go well, the rubber stays down, the helmet stays up. But sometimes, well, shit happens. Everything can seem all right, under control and perfectly normal, but suddenly and before you know it, you’re inexplicably twisted up on the ground ahead of where your bike lay sideways on the trail. As adults, we can generally gauge the severity of our crashes by whether or not our friends are laughing at us or running towards us (this doesn’t necessarily hold true for adults younger than, say, twelve, who laugh at just about everyone else’s misfortunes). Most of the time we’re lucky, and we relive the crash in all its post mortem glory with irreverence and gusto. Sometimes, though, we’re not so lucky.

I can vividly remember my first real crash on a bike. Steve Wilson, the on-again off-again friend and bully across the street got a real speed-o-meter mounted to the chrome handlebars of his bike. I was ten. We all took turns tearing up and down the street in fierce competition to determine the fastest among us. It was a game of honesty more than it was of speed, but we didn’t know that back then. When it finally got to be my turn, I started way down Adler Drive, pedaling like mad, building up speed, the wind rushing in my ears, going faster and faster than I had ever gone before. At fifteen miles an hour, as the faces of my neighborhood friends and brothers blurred past, I ran into the Ames’ lawnmower that had curiously appeared in the street and in my path. As the bike became entangled in the mower, I was catapulted over the handle bars, landing on my face in a heap a few yards ahead of the wreckage. I might have seen stars. I remember the laughter, sounding far away, muffled. I remember the atomic white flash of pain as my jaw exploded on the asphalt. I remember the hot metallic taste of blood as it flowed freely from my bitten tongue and split lip, down my shirt, splattering in fat, crimson drops on the blacktop as I staggered, howling like a wounded animal, across the street and home. It would be a few weeks before I would chew solid food again. You would never guess the magnitude of that epic childhood disaster from the insignificant scars on my chin and my lower lip. Funny thing, it seems that nearly everyone my age has the same scars. Some wounds bind.

I can vividly remember my first real crash on a bike. Steve Wilson, the on-again off-again friend and bully across the street got a real speed-o-meter mounted to the chrome handlebars of his bike. I was ten. We all took turns tearing up and down the street in fierce competition to determine the fastest among us. It was a game of honesty more than it was of speed, but we didn’t know that back then. When it finally got to be my turn, I started way down Adler Drive, pedaling like mad, building up speed, the wind rushing in my ears, going faster and faster than I had ever gone before. At fifteen miles an hour, as the faces of my neighborhood friends and brothers blurred past, I ran into the Ames’ lawnmower that had curiously appeared in the street and in my path. As the bike became entangled in the mower, I was catapulted over the handle bars, landing on my face in a heap a few yards ahead of the wreckage. I might have seen stars. I remember the laughter, sounding far away, muffled. I remember the atomic white flash of pain as my jaw exploded on the asphalt. I remember the hot metallic taste of blood as it flowed freely from my bitten tongue and split lip, down my shirt, splattering in fat, crimson drops on the blacktop as I staggered, howling like a wounded animal, across the street and home. It would be a few weeks before I would chew solid food again. You would never guess the magnitude of that epic childhood disaster from the insignificant scars on my chin and my lower lip. Funny thing, it seems that nearly everyone my age has the same scars. Some wounds bind.

There is a jaggedy outcropping known as “The Step,” a bit of techie fun protruding from the Long Loop of the McDowell Mountain Park Competitive Loops. If “The Step” were an animal on this particular day, it would have been the shark in “Jaws,” in the scene towards the end of the film where it tears Captain Quint’s boat apart. On “The Step” are fragments of my DNA. Riding with friends one afternoon last fall, I failed to clear “The Step” on my first attempt. Against my better judgment, they challenged me to a Mulligan. I have very supportive friends, you see. It’s amazing what you cannot accomplish once you’ve made up your mind that you can’t (the exact opposite holds true, of course). On my second attempt, I dead-stopped exactly where I had anticipated I would. I had not, however, anticipated raking my left leg down the toothy edge of “The Step,” my full weight bearing down on my left shin, my mind focused solely on the electrifying bolt of pain as skin and blood were torn away and claimed by that soulless rock. Using the days-old Gatorade in my Camelbak, I

There is a jaggedy outcropping known as “The Step,” a bit of techie fun protruding from the Long Loop of the McDowell Mountain Park Competitive Loops. If “The Step” were an animal on this particular day, it would have been the shark in “Jaws,” in the scene towards the end of the film where it tears Captain Quint’s boat apart. On “The Step” are fragments of my DNA. Riding with friends one afternoon last fall, I failed to clear “The Step” on my first attempt. Against my better judgment, they challenged me to a Mulligan. I have very supportive friends, you see. It’s amazing what you cannot accomplish once you’ve made up your mind that you can’t (the exact opposite holds true, of course). On my second attempt, I dead-stopped exactly where I had anticipated I would. I had not, however, anticipated raking my left leg down the toothy edge of “The Step,” my full weight bearing down on my left shin, my mind focused solely on the electrifying bolt of pain as skin and blood were torn away and claimed by that soulless rock. Using the days-old Gatorade in my Camelbak, I  rinsed out as much gravel and grit from my three new, furious gouges as I could stand, wrapped my throbbing, bloody shin in a bandana, and finished out the ride. Five months on, and it is obvious that these scars aren’t going to fade any time soon. They are passengers, permanent reminders of the power of “can’t,” purple fleshed Sanskrit forever retelling the tale of my doomed battle with “The Step.” Some wounds are self-inflicted.

rinsed out as much gravel and grit from my three new, furious gouges as I could stand, wrapped my throbbing, bloody shin in a bandana, and finished out the ride. Five months on, and it is obvious that these scars aren’t going to fade any time soon. They are passengers, permanent reminders of the power of “can’t,” purple fleshed Sanskrit forever retelling the tale of my doomed battle with “The Step.” Some wounds are self-inflicted.

Still more fragments of my DNA can be found on the Black Canyon Trail, just 2 minutes out from the Bumble Bee Trailhead. I was nearly at the end of an otherwise uneventful but enjoyable ride one balmy June morning, not two minutes from and within sight of my truck. As I ran over an insignificant rock on the trail, my balance was thrown off ever so slightly. Attempting to right myself I twisted out of my left pedal to dab the ground…which wasn’t there. I stepped instead into empty air off the outside edge of the trail, catching myself on a menacing outcrop of Precambrian schist, slicing open the back of my left calf as I did  so, clear through my skin and down to muscle. Blood was immediate. I didn’t look, knowing that if I did, my mind would probably make an ugly situation even uglier. Instead I jumped back on my bike and hammered out the remaining singletrack between me and the sanctuary of my truck, ice-cold adrenaline dumping into my bloodstream all along the way. Once at my truck I looked, confirming that it was indeed ugly: bright red arterial blood continued to pulsate from the gash and run down my leg, soaking my left sock and partially filling my left shoe. For just such unlikely events, I keep a

so, clear through my skin and down to muscle. Blood was immediate. I didn’t look, knowing that if I did, my mind would probably make an ugly situation even uglier. Instead I jumped back on my bike and hammered out the remaining singletrack between me and the sanctuary of my truck, ice-cold adrenaline dumping into my bloodstream all along the way. Once at my truck I looked, confirming that it was indeed ugly: bright red arterial blood continued to pulsate from the gash and run down my leg, soaking my left sock and partially filling my left shoe. For just such unlikely events, I keep a well-stocked first aid kit in my truck. With my sweaty bandana, I secured a few large surgical dressings to my leg and drove to the nearest emergency room, some 30 miles away, shifting and steering one-handed as I kept pressure on my calf with the other. Four hours and thirteen stitches later, I was as good as new. I am left with a scar that creates a curious offset in the tattoo encircling my left leg, a reminder to look before leaping. Some wounds are instructive.

well-stocked first aid kit in my truck. With my sweaty bandana, I secured a few large surgical dressings to my leg and drove to the nearest emergency room, some 30 miles away, shifting and steering one-handed as I kept pressure on my calf with the other. Four hours and thirteen stitches later, I was as good as new. I am left with a scar that creates a curious offset in the tattoo encircling my left leg, a reminder to look before leaping. Some wounds are instructive.

It is true that gravity is the great equalizer among riders. It doesn’t care about skill level or bike setup, and it certainly doesn’t care about pride. Despite our best abilities and efforts, there are always going to be mishaps along the way. Some recent examples from my friends and me: the shattered helmet and still-sometimes-angry rotator cuff from Rattlesnake Gulch, Utah. The blown-out MCL 2 miles into the first lap of the 24 Hours of Moab. The cracked elbow and mashed ulnar nerve from Pass Mountain, Arizona. The fractured tibia on Pistol Hill (and that excruciating 13-mile hike-a-bike out). The repeatedly torn-up right knee from South Mountain, Arizona. The progressively flattened prickly pear cactus and my progressively bruised and cactus spined rear flank from Rock Springs, Arizona (same damn cactus, multiple crashes, multiple rides). Most of the time we’re lucky, and we go on to ride another day.

And it’s also true that most wounds heal. If we’re smart, we learn, we grow, we move forward, we ride ahead. If we’re not so smart, well, we fall into the same cactus again, and again, and again, hopefully getting it right eventually.

Maybe it’s true, too, that in order to recognize and appreciate our own resilience, some wounds are necessary.

One thing is certain, though. If you want to get through this life with your sanity intact, wounds and all, laugh at yourself. Frequently. Irreverently. Like a twelve-year old. You’ll heal faster.

-PR

February 22, 2011

24 Hours in the Old Pueblo

“Holy f***ing shit,” my mind screamed while nearly being blown off my bike and into the eager arms of yet another cholla cactus by yet another punishing gust of wind. “You gotta be f***ing kidding me,” my mind moaned as my face was strafed by sideways-driven icy rain and sleet in the darkness. “Ride strong,” fellow riders would shout to me after passing on my left, their encouragement mercifully stronger than the wind. “You’re doing great,” I would call out while passing another besieged, sodden rider on their left, hoping I could pay forward the good will and vibe being given to me so generously by our other fellow riders. Songs by the likes of Crowded House, Cee Lo Green, the Temptations, Green Day, and the Spinners looped in my mind’s ear, and when I remembered to, I would sync my breathing with my cadence. “This is f***ing awesome,” my mind repeated, truthfully, emphatically, gratefully again and again.

“Holy f***ing shit,” my mind screamed while nearly being blown off my bike and into the eager arms of yet another cholla cactus by yet another punishing gust of wind. “You gotta be f***ing kidding me,” my mind moaned as my face was strafed by sideways-driven icy rain and sleet in the darkness. “Ride strong,” fellow riders would shout to me after passing on my left, their encouragement mercifully stronger than the wind. “You’re doing great,” I would call out while passing another besieged, sodden rider on their left, hoping I could pay forward the good will and vibe being given to me so generously by our other fellow riders. Songs by the likes of Crowded House, Cee Lo Green, the Temptations, Green Day, and the Spinners looped in my mind’s ear, and when I remembered to, I would sync my breathing with my cadence. “This is f***ing awesome,” my mind repeated, truthfully, emphatically, gratefully again and again.

The “24 Hours in the Old Pueblo” race was finally here, and by 9:30 Saturday night, I was deep into my third lap. By then, it had been raining for about three hours. James B. had come in from his second lap cold, soaked and stoked. Seems James is always stoked. His enthusiasm is catching, infectious. It encourages me to push myself, like the day at Estrella, riding with James and his wife Becky, when I found the will to make it to the top of the saddle in one push, or when I powered to the top of a slickrock hoodoo while riding with them in Moab, or when we pre-rode Spur Cross in prep for an upcoming race, there was James prodding me on, eager for me to see my own progress, always providing the levity required in circumstances that test one’s mettle. Stoked is a good mindset to have, and James has it in spades. This particular unforgiving night, James’ “stokedness” encouraged me to get back out there for my next lap again and again, and by the end of my third lap, I was committed to helping my teammate reach his goal of most miles he had ridden in a single event, no matter what it took. The wind — that insane, relentless wind — continued to whip through the landscape, blowing away tents, RV awnings, and in some cases, entire teams.

The “24 Hours in the Old Pueblo” race was finally here, and by 9:30 Saturday night, I was deep into my third lap. By then, it had been raining for about three hours. James B. had come in from his second lap cold, soaked and stoked. Seems James is always stoked. His enthusiasm is catching, infectious. It encourages me to push myself, like the day at Estrella, riding with James and his wife Becky, when I found the will to make it to the top of the saddle in one push, or when I powered to the top of a slickrock hoodoo while riding with them in Moab, or when we pre-rode Spur Cross in prep for an upcoming race, there was James prodding me on, eager for me to see my own progress, always providing the levity required in circumstances that test one’s mettle. Stoked is a good mindset to have, and James has it in spades. This particular unforgiving night, James’ “stokedness” encouraged me to get back out there for my next lap again and again, and by the end of my third lap, I was committed to helping my teammate reach his goal of most miles he had ridden in a single event, no matter what it took. The wind — that insane, relentless wind — continued to whip through the landscape, blowing away tents, RV awnings, and in some cases, entire teams.

I came in from my third lap exhausted. Given the choice between riding in rain or riding against wind, I will choose rain every time. As I began climbing the High Point Trail segment of the course on that third lap — you know the part of the trail I’m referring to, where you can almost smell the wet vinyl canvas of the relay tent only one mile and one climb and one rock drop away — sleet mingled with the rain, and driven by 30 mile-per-hour gusts it stung my face like bees. By the time I reached Sassy’s grave, my hands had gone completely numb; braking was now by instinct and luck. I took the bypass around “The Drop” this time in the off chance that I might skid down that rocky face on MY face if I made one false move with my useless hands. Yet, while this brutal onslaught of wind-driven rain and raw temperature sapped my energy, turning my legs to rubber, my hands to clay and my resolve to shreds, it never stripped me of the euphoria of being in the event, being in the moment, being a part of something so much bigger than my typical weekend rides, and being part of a team committed to one common purpose. Despite the cruelty of the weather that night, my euphoria was only amplified by the darkness.

When I arrived back at the relay tent to hand the baton off to James, we decided for safety’s sake to take a few hours to warm up, take in some carbs, and mentally prepare for what lay ahead. We headed back to camp and our support crew – Becky, my partner Mike, and James M. from Exhale Bikes. Mike had our camper heater set to blazing and had brewed a pot of hot coffee to warm us up. He toasted up some bagels as I relived the trials and tribulations of my latest lap. We all talked through the pros and cons of taking a few hours to regroup, and agreed that a few hours would do us all some good. We were confident that we could break for a couple hours and still meet our goals. But as I bit into my bagel, now slathered with peanut butter, James decided to ride. Before I had been back twenty minutes, James disappeared into the night on his third lap, assuring us he’d be all right.

My alarm went off at 3 a.m. My plan was to be dressed and back on the trail by 4. James had gotten back around midnight, and as I hit the trail for another lap, now wet and slippery in spots, sticky in others, I was grateful that the wind had died down even as a wind-torn fretwork of clouds played chase with the full moon above. The desert after a rain is one of the most singular scents ever conjured, and one that I love: earthy, peppery, pungent, alive. While this fourth lap would prove to be my slowest, it would also be my favorite. For reasons I cannot explain, it seemed to me that the world just fell away, that I was alone on the trail, alone in the desert, alone in the world, and I was okay. There was no existence beyond that fragile cocoon of light in which I rode. Though it was my fourth time around the course, parts of it seemed completely new, more fun than before, more colorful even in the monochrome light cast by my headlamp.

And then, I hit the High Point Trail for the fourth time.

It was as if some unseen hand flipped the switch back on to that ghastly wind, and I found myself jarred back to reality, back to simply enduring and pedaling and cursing and laughing at myself for the futility of my profanities.

Suddenly the world snapped back in place around me. I was no longer alone on the trail, and was passed by riders again offering encouragement. As before, I paid those vibes forward as I passed others, and found strength in these little kindnesses along that fourth climb up to Sassy’s. On the approach to the relay tent, the racecourse passes through 24 Hour Town, and even at this early hour, there were die-hards along the trail to rally us on, cheer us forward, and welcome us home.

The sun rose on James’ fourth lap, and all was light – and of course windy – for my fifth. Up to this point, I had been lucky. This course has acquired a notorious reputation for frequent assaults at the hands of the dreaded “jumping cholla” cactus. To hear some describe it, the cacti along this course actually have willful intent to do harm to bike tires and riders alike. In truth, the jumping cholla cactus is no laughing matter. If unfortunate enough to have a cholla ball, each armed with hundreds of hateful spines, grab hold of exposed skin, removal often requires pliers to rip the back-barbed spines from the flesh. Earlier, out on my first lap, I happened upon the race’s first cactus victim: a woman on the Corral Trail who had face-planted into a cholla. As I passed, several riders who had come to her aid were attempting to remove perhaps two dozen of those evil spikey balls, the air heavy with the sound of her screams as another was ripped away (I found out later she had been taken by stretcher back to the first aid tent, where the rest of the spines were pulled, and she actually resumed the race). My tires had been spared such a prickly fate, but if it’s not one thing, it’s another, or so the adage goes.

Immediately after cresting the “Fifth Bitch,” I had picked up enough speed to catch appreciable air off the water-bar on the backside. What I could not see until I was already airborne was the ill-placed boulder right in the sweet spot of my intended landing. There was nothing I could do, and as the nanoseconds ticked lazily by I was sure that this OTB, as spectacular as it was about to be, would probably be my last. I wasn’t going to ride after this one. I wouldn’t be able to. Through sheer mind control, somehow I managed to pull the front wheel up just high enough to avoid the rim-crushing full-stop that I expected, and instead glanced the front off the rock and back tire harder across the back of this monster. No sooner had I realized that I was still alive and still bombing downhill than I also realized I had most likely pinch-flatted the front (I know, I know, this is where you, the reader, heckle me with outbursts of the virtues of going tubeless). I stopped at the crest of the “Sixth Bitch” to confirm two things: first, my front tube was indeed hemorrhaging air and green slime, and second, I had left my spare tube and multi-tool in the kit strapped to my other bike. A wave of despair swept over me as I realized that not only might I have to walk the remaining 13 miles of this lap, but worse, my forgetfulness would probably cost James his goal. And then along came Single Speed Pete.

Immediately after cresting the “Fifth Bitch,” I had picked up enough speed to catch appreciable air off the water-bar on the backside. What I could not see until I was already airborne was the ill-placed boulder right in the sweet spot of my intended landing. There was nothing I could do, and as the nanoseconds ticked lazily by I was sure that this OTB, as spectacular as it was about to be, would probably be my last. I wasn’t going to ride after this one. I wouldn’t be able to. Through sheer mind control, somehow I managed to pull the front wheel up just high enough to avoid the rim-crushing full-stop that I expected, and instead glanced the front off the rock and back tire harder across the back of this monster. No sooner had I realized that I was still alive and still bombing downhill than I also realized I had most likely pinch-flatted the front (I know, I know, this is where you, the reader, heckle me with outbursts of the virtues of going tubeless). I stopped at the crest of the “Sixth Bitch” to confirm two things: first, my front tube was indeed hemorrhaging air and green slime, and second, I had left my spare tube and multi-tool in the kit strapped to my other bike. A wave of despair swept over me as I realized that not only might I have to walk the remaining 13 miles of this lap, but worse, my forgetfulness would probably cost James his goal. And then along came Single Speed Pete.

“Hey Phil, everything okay?”

“Not really,” I sighed, “I snakebit my front tube and I left my spare back at camp.”

“Here, use mine,” Pete said as he got off his bike to assist. “It’s all good.”

In addition to the tube, Pete offered me yet more words of encouragement that set the tone for the rest of my lap, and he took off as I put my wheel back together.

I made it back to the relay tent at 9:23 a.m. and handed the baton off to James. In that moment, the dice were cast, and James would complete a double lap to claim his personal goal of most miles ridden in a single event. It was a great achievement, and I am happy that I was there to witness it. I would also set many personal benchmarks in this race: first duo (the first of many more with James), first 24OP, and most miles I had ever ridden in a 24-hour period.

I am still sifting through my thoughts and impressions of the race, and while it may take me a while longer to accurately define the meaning and magnitude and fix it in my memory, I can say without equivocation that for the most part, mountain bikers are one incredible, supportive, competitive, rowdy, bawdy and encouraging collective. And we’re a generous bunch. We offer unsolicited words of encouragement to other riders we may not yet know. We offer up our only tube to a fellow rider who forgets to bring their own. We break bread together and are quick with a beer. We ride for charity. We ride for sport. We ride to participate. We ride to win. We ride for the love of it and the joy of it. We ride for our sanity AND our insanity. We ride for the camaraderie and kinship that come from sharing the trail with friends — those we know, and those we don’t yet.

Man, I can’t wait to ride with you all again next year.

-PR

February, 2011

February. The shortest month, and in many parts, the coldest, or so it seems. February was always the beginning of the “mud season” where I grew up. It was the time of year when late winter storms would prowl the nighttime skies, cold days would yield to warmer, and every now and again you’d catch a whiff of earthy springtime carried by a warm breeze as it swept above the wet, red ground of my Alabama childhood. Pretty soon, the dogwoods would flower out, the redbuds would explode in pink and violet, and mud season would harden into “barefoot season.” And barefoot season meant bikes.

Where I grew up on the outskirts of Montgomery, Alabama, the neighborhood ended where the old-growth pine and hardwood forest began. It was a surviving patch of forest that has long since been scraped clean and overrun with all the improvements of suburbia. But when I was a kid, it was a magic place. My friend Richie and I would ride our Huffys down to the dead-end on East Riding Road, ride around the white-washed wooden barricade, and disappear into another world. Catoma Creek meandered through these woods, shaded by ancient oaks and hickories festooned with Spanish moss; this was the realm of water moccasins and armadillos and snapping turtles and monsters and mystery and legend. We never questioned how the red dirt trails through the woods came to be, they just WERE. And we would ride them all day, day after day. They had names like “dirt ditch trail,” or “pipe trail,” or “pine tree trail,” or “tree fort trail,” and collectively they would create the map on which some of my favorite childhood memories are drawn.

I began this journey in February of 1966. Forty-four laps around the sun and counting, about to begin the next. Looking back, it’s funny how the circles of life wander through time, ripples on a pond growing ever larger, bouncing off the shore, or rock or branch, bouncing back to ourselves, reminding us of what we were, where we come from, who we are, and where we might yet go. I am no longer that uncomplicated kid on a Huffy. Alabama is a long way back, a previous life, even. Oaks and hickories and towering pines have been replaced by saguaros and palo verdes and creosote bushes; water moccasins and armadillos replaced by rattlesnakes and javelina; the Huffy replaced with a Rockhopper (and the Marathon, when I am feeling charitable towards my GT). I still skin my knees, crash, pick myself up (and yes, sometimes with a tear in my eye), and I still mercifully lose myself on my bike. So into lap #45 I go, new circles, new trails, new adventures.

And Richie? Well, we don’t replace our friends, and why would we want to? We do, however, lose touch, the distance doled out in the passage of time, the expanse of geography. I don’t know where he ended up or who he became. But I’m pretty sure that if you asked him about some of his favorite childhood memories, they would involve a bike, a path or two along Catoma Creek through those magic woods, and he might even remember a kid named Phil.

-PR

January, 2011

A week or so before 2010 drew to a close, people started posting their 2010 ride totals on one of the boards. It impressed me that as a group we log the miles and ascend the feet we do, and some of you really threw up some incredible numbers. I did a poor job of keeping a good tab in 2010, what with switching bikes and bike computers and fumbling around with an old relic of a GPS (that I now have up and running and it really does work, honestly!). I am not one for making resolutions at the beginning of a new year, not anymore, anyway. I mean, come on. I lost the weight. I quit the smoking. I cut way back on the drinking. I shower nearly every day now, mostly. I gave up doing the smell-test to see what was wearable in my dirty laundry. There just aren’t many more resolutions to make and to keep. I’ve done pretty well overall. But I will make one for 2011: I resolve to do a better job logging my biking exploits, and for no other reason than to look into the mirror as 2011 draws to a close in 11 months and change.

I wrapped up 2010 with a Hawes Epic with my buddy John. It was cold, never got above 41 degrees, though the weatherman promised 53. John and I were going to ride trails in the Hawes system and head over to Pass Mountain via Twisted Sister and Wild Horse, which we almost did. But we skipped Pass Mountain to save for another day, but did all the rest, looping completely around the the Usery range. In all, we rode 31 miles, give or take, and climbed a total of 3,400 feet. Not too shabby.

And I conquered Cardiac Hill for the first time. John witnessed it.

The New Year started out sleeping in, but sped up quickly. Rode Hawes again, the McDowell Loops a few times, Lost Gold Mine and the “K-Trail” that another buddy, John, turned us on to, rode Quartz Ridge over in Gold Canyon, the Arizona Trail Picket Post section twice, Papago, snuck in a couple after-work rides at South Mountain, and rode much of the AZ Trail Jamboree ride in Tucson. And already, I am at 135 miles and nearly 13,500 vertical feet of ascent. I am amazed at how fast the numbers wrack up, and pleased to see my own progress.

I joined the Mountain Bike Association of Arizona and will be racing in Category 3 40-49. I'll be wearing a Team Exhale jersey. Should be a fun season! I wanted to try racing years ago, but was too intimidated by other riders far better than I, too self conscious about the inferiority of my rig compared to the new bikes that were out there. But as I get older, I realize that it’s not about any of that. It’s about testing my own mettle, gauging my own progress, and getting out there with my friends who push me and challenge me and help me evolve as a rider and as a person. I don’t regret not having raced years ago, but instead I am happy I am giving racing a try now.

Hell, I am just happy to be riding again.

-PR

December 20, 2010

Man, time flies. The Moab 24 seems like both last week and last year, the Black Canyon AZ Endurance Series ride forever ago, and 24 Hours in the Old Pueblo is fast approaching.

Some thoughts...

Using Phoenix as a center point, and scribing a 100-mile radius around the city, you capture a hundred or more of some of the Southwest’s best single track! Of course, there are the obvious and eternal outliers – Moab, Crested Butte, Durango, Park City, and Whistler (never been, but nods must go to a place that looks like it was sprung from the imagination of Tolkien). Yes, we’ve got Desert Classic. Mormon, National, Alta. McDowell Loops. Hawes. Goat Camp. Mesquite. FINS. Estrella Loops. AZ Trail – Alamo Canyon. Black Canyon Trail (ALL of it). Lost Gold Mine. Highline. Trail 179. Trail Two-Sixty. Sedona (I won’t even attempt a list!). Pass Mountain. Pemberton. And at least a hundred others I haven’t ridden yet, or don’t remember right now, from super-chunk tech to easy slow burns, fast and furious descents to “brain surgery better-pick-a-winner-line-or-OTB” challenges.

Hazards? We got ‘em. Lightning bolts. Hailstones. Rattlesnakes. Saguaros. Cholla balls. Mine shafts. Flash floods. Cows. Red rock stair steps. Ancient granite waterfalls. Javelina. Cat claw. Knife-edged schist. Boulders with evil 26-inch spaces in between. Bats. Night owls. Scenery—yeah, I have to throw that in as well, because it’s not hard to get caught up in the sweeping vistas that so may of our trails afford, and very easy to lose control as a result. Advice? Pull off the trail and smell the roses. They are sweet indeed.

I got my first mountain bike in 1990. It's fair to say, I think, that I didn't actually learn to "ride" until 1993. I was new to Arizona, new to life in a foreign land (I was a longhair punk from Pennsylvania), trapped and suffocating deep inside my own head, having recently lost my dad to cancer, and now watching my mom begin her awful downward spiral to her cancerous death. I was enrolled at ASU, eager to run away from overwhelming sadness, eager to be “someone else,” eager to earn my masters in geology and get on with my life, as if life had a “Start Button” that came with the degree. I hadn’t yet learned that this was not the case.

If riding was my salvation, then single track and twisted unnamed sunburnt canyons were my church. The wind in my ears drowned out the constant chatter, and the trail ahead demanded my full attention. It was the only time I could shut down all but two primal instincts: survival and ecstasy. As I look back over the past two decades, I can recall some of the ups, some of the downs, but I can remember clearly all of my epic rides - North Rim Grand Canyon; Poison Spider Mesa to Portal Trail; Death Valley and The Maze to name just a few. And yet, while these have been some of the happiest times of my life, depression has always ridden shotgun, an unwelcome and jealous companion. Except when I get on the bike, there’s only room for one: me.

As the years progressed, I rode less and less, always telling myself that I’d ride tomorrow…then next week…then next month…then next fall…then I finally just quit making empty promises altogether. My bike, a ’96 Rockhopper, waited patiently, alone in the garage, knowing the day would come when we’d once again share the joy of riding.

In the spring of 2010, as I approach the age at which my dad first fell ill, I decided enough was enough. It’s not that I fear death, no more then the next guy I’d guess. I just refused to live like my father prior to his death sentence—out of shape, sedentary, vaguely sad. Getting back on the bike was not to run from death. It was, and is, to enjoy life to its fullest, to wring out every last inch from this crazy thrill ride. “If I lose a few pounds,” I thought, “so much the better.” And the fun and fat tire madness I had once enjoyed have only gotten better, stronger, more meaningful.

Since getting back out to the trails, I have become reacquainted with one of the simplest joys there is: riding. I have become reacquainted with some dear friends, have made new friends, and have rediscovered a whole wide world that never really left me. It has been a prodigal welcome, a homecoming, a reawakening. Salvation 2.0. Grateful to my partner Mike for his unwavering love and for putting up with my new habits (even if I myself don't fully understand them), to old and new friends for sharing themselves and for sharing with me some of the best single track around. And to the family I have cobbled together through the years, people who know me and love me and challenge me more than my own clan ever could have. These people have encouraged me to define who I am, to become the man I am today, flaws and triumphs and all. Thanks for standing by me through the years. I ride for you as well.

-PR

ended up with syrup. NOT this time! The jam from the first batch set beautifully, and we ended up with a case and a half of jam! We had a lot of leftover syrup which I froze to can the following weekend.

ended up with syrup. NOT this time! The jam from the first batch set beautifully, and we ended up with a case and a half of jam! We had a lot of leftover syrup which I froze to can the following weekend.

Let’s be honest. Rattlesnakes can be scary. Sometimes they scare me. They can make my heart rate spike, they can flip some fear-response switch in my primordial brain. But rattlesnakes don’t go out of their way to bite people. First of all, it takes a rattlesnake a lot of time—days—and energy to generate venom, and a rattler would much prefer to use it to capture its next packrat or lizard or baby bunny than to waste it on gangly, two-legged ungraceful monstrosities many, many times its size that it could never possibly eat. They strike to eat and if necessary to defend, but they do not strike to attack. They are not strategic, cunning man eaters. Second, rattlesnakes can only strike with accuracy within a distance 2/3 its length. In order to get bit, a person must place their hands (the most usual limb to get bitten, for suspicious reasons) within 2 feet of a typical full-grown rattlesnake. Third, a rattlesnake has no arms, no legs, no other possible way to defend itself other than through its bite. Don’t give a rattlesnake the opportunity, and it isn’t going to bite. Finally, in more than half of snakebite incidents, the “victim” was doing something stupid. And getting close enough to a rattlesnake in order to kill it is stupid.

Let’s be honest. Rattlesnakes can be scary. Sometimes they scare me. They can make my heart rate spike, they can flip some fear-response switch in my primordial brain. But rattlesnakes don’t go out of their way to bite people. First of all, it takes a rattlesnake a lot of time—days—and energy to generate venom, and a rattler would much prefer to use it to capture its next packrat or lizard or baby bunny than to waste it on gangly, two-legged ungraceful monstrosities many, many times its size that it could never possibly eat. They strike to eat and if necessary to defend, but they do not strike to attack. They are not strategic, cunning man eaters. Second, rattlesnakes can only strike with accuracy within a distance 2/3 its length. In order to get bit, a person must place their hands (the most usual limb to get bitten, for suspicious reasons) within 2 feet of a typical full-grown rattlesnake. Third, a rattlesnake has no arms, no legs, no other possible way to defend itself other than through its bite. Don’t give a rattlesnake the opportunity, and it isn’t going to bite. Finally, in more than half of snakebite incidents, the “victim” was doing something stupid. And getting close enough to a rattlesnake in order to kill it is stupid.

I often make the case that when we are out on the trail, we are in the rattlesnake’s living room, also the realm of the Gila monster, the scorpion, the javelina, the tarantula, mountain lion, the jumping cholla, all things elegant and beautiful and toothy and prickly and sometimes venomous. It begs the question, then, about how and where we humans fit in to this picture. As I ride, I have no good answer.

I often make the case that when we are out on the trail, we are in the rattlesnake’s living room, also the realm of the Gila monster, the scorpion, the javelina, the tarantula, mountain lion, the jumping cholla, all things elegant and beautiful and toothy and prickly and sometimes venomous. It begs the question, then, about how and where we humans fit in to this picture. As I ride, I have no good answer. ballooning, sending skyward a single strand of the most delicate, pure gossamer web, stronger than steel, catching the breeze and flying off to new lives, new worlds, new single-parenting adventures. At some point in my childhood, I remember reading about the early days of the

ballooning, sending skyward a single strand of the most delicate, pure gossamer web, stronger than steel, catching the breeze and flying off to new lives, new worlds, new single-parenting adventures. At some point in my childhood, I remember reading about the early days of the  Riding a bike is not without risk. It takes a certain amount of skill and coordination to keep the thing balanced and moving forward. Most of the time things go well, the rubber stays down, the helmet stays up. But sometimes, well, shit happens. Everything can seem all right, under control and perfectly normal, but suddenly and before you know it, you’re inexplicably twisted up on the ground ahead of where your bike lay sideways on the trail. As adults, we can generally gauge the severity of our crashes by whether or not our friends are laughing at us or running towards us (this doesn’t necessarily hold true for adults younger than, say, twelve, who laugh at just about everyone else’s misfortunes). Most of the time we’re lucky, and we relive the crash in all its post mortem glory with irreverence and gusto. Sometimes, though, we’re not so lucky.